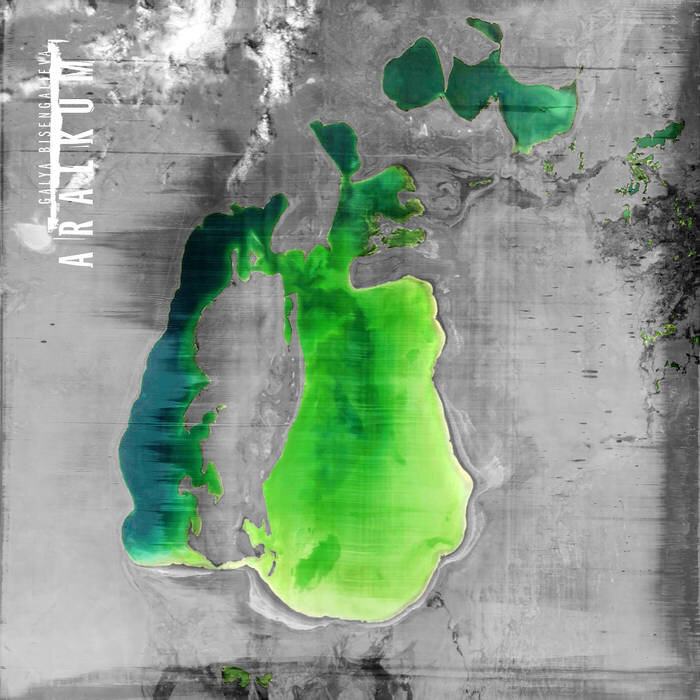

Galya Bisengalieva

Aralkum

by David Cortés

Hailing from Almati, in Kazakhstan, violinist Galya Bisengalieva brings us her first album, a work where the sadness for loss is tangible right from the beginning until the last note.

Trained at the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music, and leader of the London Contemporary Orchestra, Galya Bisengalieva can go from playing compositions by Brahms or Scelci, to collaborating with Radiohead or Pauline Oliveros; but, in Aralkum, she has finally created a space for her voice to rise and sound as loud as possible.

The album talks about how one day the Aral Sea, as a result of the works of man, began to dry up to become the youngest desert in the world. Bisengalieva dug into her memories, used field recordings from the region and hooked up her violin to electronic circuitry to portray the disaster.

“Aralkum”, the initial track, unfolds the axis of what we are going to find on the way: expansive drones created with the violin interrelated with electronics and those field recordings that are like fragments of distant memories. The track begins with something similar to a murmur, it is an abstraction built with a series of little musical sounds; suddenly, the atmosphere changes, becoming clearer with the entrance of a violin, lamenting and moaning over the destruction that it is witnessing. The field recordings are like heavy footsteps from a silent giant, sweeping and devastating, gradually affecting the landscape, leaving it unrecognizable; meanwhile, the violin imitates what could be interpreted as the shrieks of a lonely, grieving seagull.

"Moynaq" was a port city, and here, the wind marks the transition; the violin is not plaintive, it describes a still life, it mimics the echo of a voice that recalls open spaces and tells of sad and desolate glances that stare at the horizon and seek the lost; as the track progresses, the feeling of emptiness grows.

Another town abandoned by the Aral Sea disaster was “Kantubek”. Here the lamentation continues as we are transported to the center of nowhere and feel how the pain gradually surrounds us; a swirl of earth rises where there was a slight swell before, and the intensity of the drones increases as the violin seeks to play a requiem.

Aralkum is lavish in imagery: as the compositions go by, one cannot stop thinking about how, not that long ago, that space was full of life, and now there’s nothing but death, and in “Barda-Kelmes” (a word that roughly translates into “who goes there does not come back") the wind vibrates in a different way. The night has come and the stars and the sigh of many lost hours are heard. A pizzicato moves around a mute rhythm changing the register in "Zhalanash"; the music seems to be enlivened with expansive harmonies, and when we get to "Kokaral", we have an aerial image that lets us see the desolation, the depths of the devastation and the magnitude of the disaster. There is nothing more to say about the album other than prepare for 34 minutes of intense, vivid emotions that should be taking into consideration for our future’s sake.